TRADITIONAL HERO vs ANTI-HERO: The Dark side of Heroism, Why Anti-Heroes Rule

From Fairy Tales to modern movies, we always cheer for the hero who saves the day and never tells a lie.

But lately, our favorite "heroes" look a lot more like... well, villains.

Why do we cheer for the guy who breaks every rule in the book just as loudly as we cheer for the one who follows them? Today, we’re breaking down the fundamental differences between the Traditional Hero and the Anti-Hero—and why we might actually need both.

Why do we cheer for the guy who breaks every rule in the book just as loudly as we cheer for the one who follows them? Today, we’re breaking down the fundamental differences between the Traditional Hero and the Anti-Hero—and why we might actually need both.

THE TRADITIONAL HERO

Let’s start with the classic. The Traditional Hero is built on altruism and a moral compass that points true North, 100% of the time.

Key Characteristics:

-

The Internal Code: They have a strict set of ethics (think Batman’s "no-kill" rule or Spider-Man’s "responsibility").

-

Self-Sacrifice: They’ll put themselves in harm's way for a stranger without hesitation.

-

The Symbol: They aren't just people; they represent an idea—Justice, Hope, or Honor.

In these stories, the conflict is usually External. It’s the Hero vs. The World. We love them because they represent the best version of what humanity could be. They are the light in the dark.

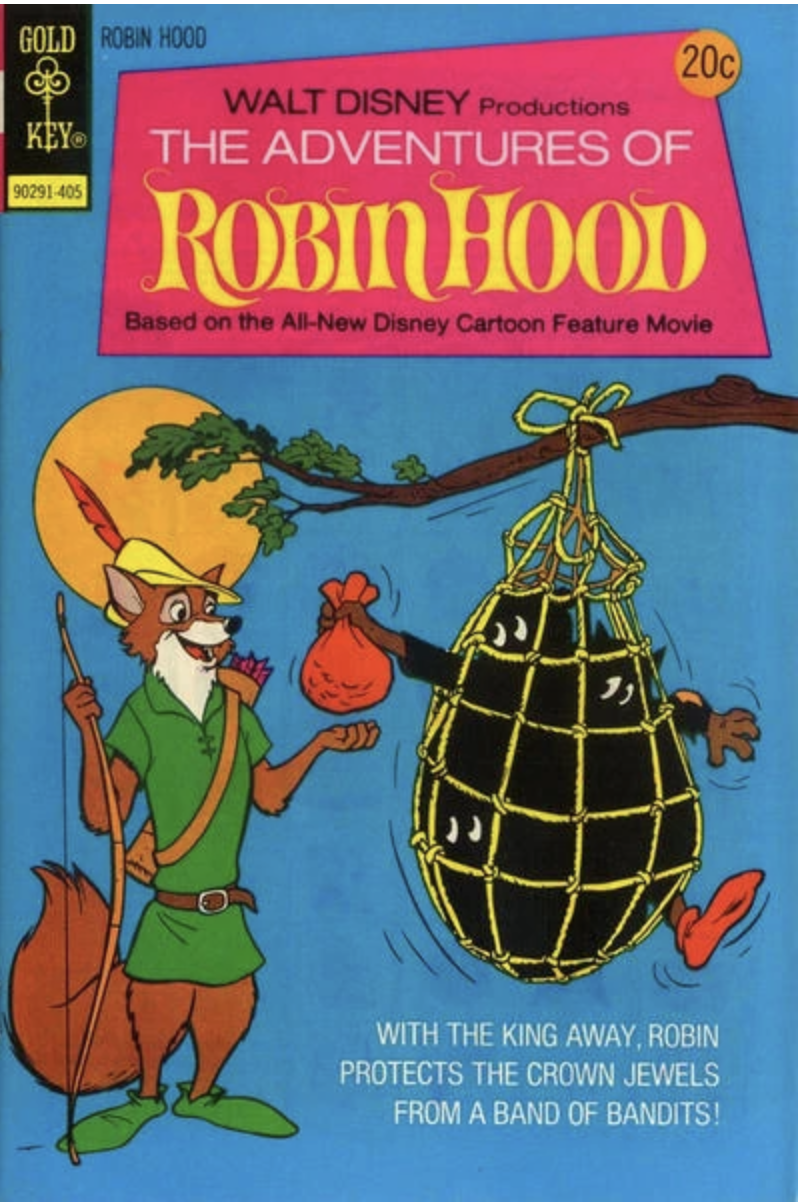

To better understand the differences between a traditional hero and an anti-hero, I use two icons, actually, three icons of the American Western genre to compare. For the traditional hero, the classic and legendary John Wayne, and for the anti-hero, the messy Tuco, and the cynical, cool Blondie, from my favorite movie; The Good The Bad and The Ugly by Sergio Leone.

John Wayne represented the American Ideal—noble, community-minded, and morally clear.

THE TRADITIONAL PILLAR: JOHN WAYNE

In almost all of his films (Rio Bravo, Stagecoach, The Alamo), John Wayne plays a character who is a symbol of civilization.

-

The Moral Code: Even when his characters are "rough," they operate under a strict code of honor. He protects the weak, respects women, and usually wears a badge or leads a cavalry.

-

The Community Hero: Wayne’s characters usually fight for something larger than themselves—a town, a family, or the future of the American frontier.

-

Visual Style: He is clean-shaven, stands tall, and uses his fists or a rifle. Violence is a tool used only when necessary to restore order.

-

The Exception: In The Searchers, Wayne played Ethan Edwards, a much darker, obsessive character.

This role actually paved the way for the grittier anti-heroes that followed

THE ANTI-HERO (THE HUMAN)

Now, let’s get messy. Enter the Anti-Hero. This character lacks the conventional "heroic" qualities like idealism or morality.

The Three Flavors of Anti-Hero:

-

The Pragmatist: They do the right thing, but they use "wrong" methods. (Think: The Punisher).

-

The Reluctant Hero: They don’t want to help, but they end up doing it anyway—usually for a personal reason. (Think: Han Solo in the beginning).

-

The Moral Gray: They are motivated by self-interest, revenge, or even survival.

Unlike the traditional hero, the Anti-Hero’s biggest conflict is often Internal. They are fighting their own demons as much as they are fighting the villain. They don’t represent what we should be; they represent who we actually are—flawed, angry, and sometimes selfish.

FEAUTURE TRADITIONAL HERO ANTI-HERO

Motivation Duty / JusticePersonal / Survival

Methods Noble / Legal Whatever works

Moral Outlook Black & White Shades of Gray

Public Image Loved / Respected Feared / Misunderstood

THE COOL CYNIC: BLONDIE (THE GOOD)

Played by Clint Eastwood, "Blondie" is the bridge between a hero and a mercenary. He is "The Good" only because he’s less sadistic than the "Bad" (Angel Eyes).

-

Motivation: Unlike John Wayne, Blondie isn't trying to save a town. He is after $200,000 in buried Confederate gold.

His primary driver is profit. -

Moral Ambiguity: He runs a scam with Tuco where he "captures" him for bounty money, saves him from hanging at the last second, and splits the cash.

This is a far cry from John Wayne’s law-abiding sheriffs. -

The "Silent" Warrior: While Wayne was talkative and didactic (giving advice on how to be a man), Blondie is taciturn.

He speaks with his gun. -

The Heroic Glint: We call him "Good" because he shows small flashes of humanity—like giving a cigar to a dying soldier.

He has a "professional" code, but not necessarily a "moral" one.

THE CHAOTIC SURVIVOR: TUCO (THE UGLY)

Tuco (Eli Wallach) is the ultimate subversion. In a John Wayne movie, Tuco would be a side villain or a comedic nuisance to be locked in a cell. Here, he is a co-protagonist.

-

The "Ugly" Truth: Tuco represents the desperation of the West.

He is a bandit because he was poor and had no other choice. He is "Ugly" because he is a raw, unpolished reflection of human greed and survival. -

The Comic/Tragic Balance: He is funny and loud, but he’s also a killer. His relationship with Blondie is based purely on a "mutual need" for the gold.

-

The Lack of Code: Tuco will beg, plead, scream, and betray anyone to stay alive. He doesn't care about honor; he cares about breakfast and gold.

COMPARISON SUMMARY

John Wayne is who we hope we are; Blondie is who we wish we were (cool and untouchable); and Tuco is who we probably would be if we were actually stuck in the middle of a desert during a war.

THE MOTIVATION: HONOR VS GOLD

In a John Wayne movie, the plot is usually driven by a moral necessity. He’s protecting a ranch, saving a captive, or holding a jailhouse against a lynch mob. He represents order.

But look at Blondie and Tuco. They aren't trying to build a civilization; they’re trying to rob one. They are wandering through the middle of the American Civil War, and they couldn’t care less about the North or the South. They only care about $200,000 in gold. While Wayne fights for a flag, Blondie and Tuco fight for currency.

THE METHOD: THE FAIR FIGHT VS THE SCAM

John Wayne’s characters usually give you a chance. There’s a sense of "Fair Play." If you draw on him, he’s faster, but he’s rarely going to shoot you in the back.

Now, look at the opening of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Blondie and Tuco are running a bounty-hunting scam. Blondie "turns in" Tuco for the reward money, then shoots the rope right as Tuco is being hanged so they can escape and do it again in the next town. It’s brilliant, it’s funny, but it is deeply "un-heroic" by traditional standards.

THE "UGLY' REALITY OF THE ANTI-HERO

Then there’s Tuco. In a John Wayne world, Tuco is a villain. He’s a thief, a liar, and a murderer. But in the Anti-Hero era, he becomes our POV character.

There’s a scene where Tuco confronts his brother, a priest, who judges him for his life of crime. Tuco fires back, saying he became a bandit because the only other choice was to starve. This adds pathos. John Wayne is the hero we wantto be; Tuco is a reminder of the desperate things people do when they have nothing.

When you move from John Wayne to Blondie and Tuco, you’re moving from Idealism to Realism. Wayne tells us that the West was won by "Good Men." The Good, the Bad and the Ugly suggests the West was won by the people who were simply too tough—or too greedy—to die.

CONCLUSION

Ultimately, the anti-hero is so compelling because they bridge the gap between who we are and who we wish we could be. While the traditional hero represents an impossible standard of perfection, the anti-hero offers us something much more valuable: recognition. They are a mirror for our own frustrations, our selfish impulses, and our messy attempts to navigate a world that isn't always fair. We like them because they don't have to be "good" to be right; they prove that you can be broken, cynical, and deeply flawed, yet still possess a spark of humanity that chooses to do the right thing when it truly counts. In the end, we don't just watch anti-heroes for the action—we watch them because they make our own imperfections feel a little more like a superpower.

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS ARTICLE, FILL FREE TO WATCH MY VIDEO HERE BELOW 🙂